The facts about the conquest of Native Americans continue to become more widely known, and the indigenous people of today still offer their testimony to the world, not only about the past but about continued oppression right now. Recently, though, I’ve been thinking about the effects of the conquest on the minds and hearts of white Americans, as reflected in the culture, and especially in the movies.

Native Americans have been depicted in film since the beginning. Among the earliest of Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope films was an 1894 clip of Lakota Indians from Buffalo Bill’s "Wild West Show" reenacting the Ghost Dance.

D.W. Griffith’s The Battle at Elderbush Gulch from 1914 features the most enduring theme: a family is trapped in a house surrounded by marauding Indians until the cavalry comes to the rescue. The Indian was the threatening other, a being completely alien to our way of life, with a painted face and feathered headdress, a “savage” as they called it. Fear justifies hatred, which justifies killing.

The Indians were most often, as in this early example, a backdrop to the drama of the white frontier people trying to make a new life. The attack of the Indians was a scary and exciting spectacle for audiences. Of all the scenes in westerns featuring Indians, this was the most typical—an aggression resisted by heroic settlers, or soldiers, climaxing with a great slaughter of Indian warriors. Taking into account the cumulative effect on viewers of hundreds of westerns throughout the decades, the average person would think that Indians were constantly attacking the whites in force, and that only the most heroic resistance to this aggression made America as we know it possible. The real story—of forced relocations, encroachments on and massacres of, native people—went untold.

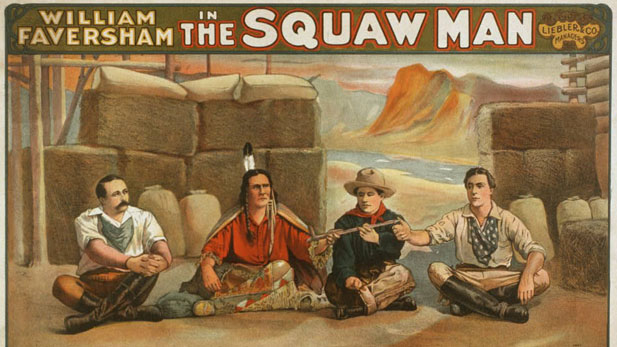

The first full-length feature made in Hollywood was Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man, also from 1914, the title containing a garbled derogatory slang term. But the picture itself brings up another curious theme—a sense of guilt about what was done to Indians, and a corresponding idealization of them. The native woman in the film, played by a Winnebago actress, saves her white man’s life twice, bears his child, but still ends up on the losing side of the plot. Later examples of this theme include the wise, stoic medicine man and the noble warrior. Of course this is better than the stereotype of the savage, but it’s still not a real human being with a personality and character flaws, only a projection of the conflicted emotions of white Americans about the nature of their heritage.

Hundreds of nations, as we are used to calling them, inhabited this land, with widely different languages, customs, physical appearances, and religions. The colonizers put them all in one category as if they were the same, while perpetuating the original mistake of calling them Indians, until it stuck. In the movies, they were almost exclusively turned into Plains Indians, usually the Sioux. Here in the Southwest, where many westerns were made, Navahos were most often the ones used as actors and extras, no matter what tribe was being depicted. And of course in John Ford’s westerns we see the supposed Plains Indians living in Monument Valley. Furthermore, if there was a prominent Indian character, he or she would always be played by a white person—everyone from Burt Lancaster to Rock Hudson and even Audrey Hepburn played Indians.

Even when a production tried, with good intentions, to be honest, there was always a certain condescension, a persistent idea that there’s something shameful about being a native. I find it interesting, because I think this is a projection of an internal shame that white America couldn’t face, a knowledge, however obscure, that their position in this land was founded on injustice. Among the better examples of this more honest kind of film was John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn, from 1964, dramatizing the criminal treatment of the Cheyenne. It seems almost like a personal atonement by the director for his part in the Hollywood Indian myth.

Little Big Man from 1970, and Dances With Wolves from 1990, were evidence of some progress because the Indian characters in these films had personalities—they were granted a fuller humanity. Keep in mind, though, that the main characters in both these movies were white. And finally there have been some films made by Indians in recent times, like Dance Me Outside and Smoke Signals, with a genuine native point of view. But there needs to be a lot more of them.

I highly recommend Reel Injun (the use of the word “Injun” is of course satirical) — it’s a 2009 documentary by Cree director Neil Diamond that explores the depiction of Native Americans in movies. Although the film tries to cover too much ground, it has enough interesting and amusing information to make it well worth seeing.

One of the persons interviewed is the late Santee Dakota poet and activist John Trudell, who at one point makes a profound statement. The myths are destructive, he says, not merely because they denigrate Native American identity, but more importantly because they deny the basic nature of people as, before anything else, simply human beings. By painting the other as an enemy to be feared and despised, thus justifying the theft of all they have, the myth fails to recognize them as human. And in the process, inevitably, we all end up losing awareness of our own humanity.

For Arizona Spotlight, this is Chris Dashiell.

You can join Chris Dashiell and Mark McLemore with their friends filmmaker Robert Loomis and photographer Pamela Sentman for a lively discussion about films from anytime and everywhere in the new podcast series "Let's All Go to the Lobby", right here on azpm.org.

Who is Chris Dashiell?

Film reviewer Chris Dashiell

Film reviewer Chris Dashiell

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.