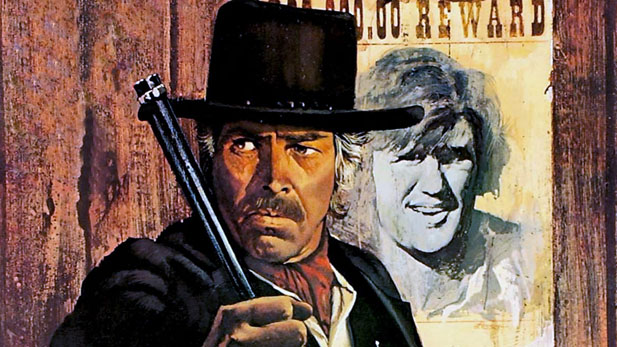

James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson play the title roles in "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid" from 1973

James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson play the title roles in "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid" from 1973

Article written by Chris Dashiell

Of all the stories about outlaws in the American West, for me the weirdest is “Billy the Kid.” Not because the facts were particularly strange, but because so much was later made out of them, mostly fictional.

The young man who called himself William Bonney was a cattle rustler involved in the famous Lincoln County Wars in New Mexico, a series of revenge killings in the 1870s that started with the murder of an English rancher for whom Billy had worked. Billy was later sentenced to hang, but then escaped from jail in Lincoln, killing two guards in the process. All told, he may have killed seven or eight men in his career. At the age of 21, he was shot dead by Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett, at one of Billy’s hideouts near Fort Sumner.

Listen:

The myth making started when New Mexico’s governor put a price on Billy’s head in 1881, the year he died. The New York Sun picked up the story, and then Billy became one of the main characters in the numerous Western dime novels published at the time. My theory is that the nickname “The Kid” caught on with the mostly younger readers of those adventures. And although these stories were supposed to be cautionary tales about criminal behavior, there was a feeling of romance about being an outlaw that was the source of much of their popularity. Dozens of movies have been made over the years about Billy the Kid—usually turning the short scrawny young man of reality into a hero or at least a leading man. A typical example of the Hollywood treatment is the movie Billy the Kid from 1941, directed by David Miller.

Robert Taylor—tall, dark, handsome, and not at all like a kid, plays Billy, who is hired by a group of rustlers to drive an English rancher out of the territory. After discovering that an old friend works for the Englishman, Billy eventually switches sides and is hired as a ranch hand. The rancher’s murder drives him to seek revenge, even though his friend, now the marshal, insists on keeping to the law.

Actor Robert Taylor seemed an unlikely choice to play Billy the Kid (1941)

Actor Robert Taylor seemed an unlikely choice to play Billy the Kid (1941)

It’s a fairly standard picture for the time, a lot of it shot in Tucson—you may recognize Sabino Canyon in some scenes. There’s the element of Billy the Kid shooting left-handed, one of the widely held beliefs about him that turned out to be false, and a very free use of elements from the Lincoln County Wars. The main idea is that Billy is a bad guy who, deep down, is really a good guy—he just needed some encouragement and understanding to go straight. This was a popular idea because audiences got to enjoy the actions of the outlaw while still feeling morally pure.

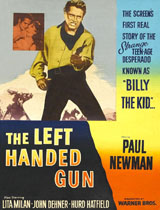

Moving ahead to 1958, we have Paul Newman starring in The Left Handed Gun, the debut film by director Arthur Penn, who would later make Bonnie & Clyde and Little Big Man. The script tries to follow, in highly condensed form, the outlines of the truth. Pat Garrett is in this one, and he makes friends with Billy and even welcomes him at his wedding. There is no evidence that they were friends in reality, but the idea that the sheriff who killed Billy the Kid used to be his friend has been a very potent element of the myth.

Here Billy is played as an inarticulate, hot-headed adolescent. Paul Newman was 32 at the time, but he looks younger. What strikes me is that the performance is a lot like the kind of sensitive, emotionally tortured young men cropping up at that time in movies featuring Marlon Brando and James Dean. The 1950s were when Hollywood really discovered the teenager, and this Billy the Kid is essentially a troubled misunderstood teen, who tries to do what’s right but can’t control his angry impulses. Another typical element is the search for a father figure that can help heal the wounded hero — first the English rancher, then Pat Garrett, both times ending in failure.

As it turns out, Billy the Kid wasn't actually left-handed, despite this movie's title

As it turns out, Billy the Kid wasn't actually left-handed, despite this movie's title

My final example is Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, from 1973 and directed by Sam Peckinpah. Here the supposed friendship between Garrett, played here by James Coburn, and Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson) takes center stage. The West has been corrupted by big money interests, the old free ways of the cowboy are doomed, and Garrett is hired by a group of cattle barons to find Billy and kill him.

The troubled youth of the 50s has now become the rebellious youth of the 1960s. Kristofferson’s Billy is an easy-going hedonistic outlaw—I hesitate to use the word “hippie” but that’s kind of what’s implied. The counterculture element is even more evident because Bob Dylan is on the soundtrack, and actually appears in a small role.

Coburn’s Pat Garrett is a tragic figure here, someone who has lost his honor and sold his soul. The film is very uneven, crammed with old western character actors that Peckinpah brought together, and there are so many gunfights and other scenes of violence that the effect is jumbled and confusing. But the feeling of loss, of an old order corrupt and dying, so characteristic of the time, is quite stirring, and the scene where Garrett shoots Billy, and then his own image in the mirror, sums up in a way Peckinpah’s vision of the West.

It’s remarkable how all these films about Billy the Kid reflect and amplify the eras in which they were made, and how such a small group of mythic elements could be expanded in so many ways. That’s how the movies transform history into legend. In this case, the Western outlaw ended up representing a lost ideal of American freedom. Maybe someday a film will be made about the real story of Billy the Kid—but I doubt it.

Who is Chris Dashiell?

Film reviewer Chris Dashiell

Film reviewer Chris Dashiell

Chris Dashiell has been writing about movies for seventeen years, serving as the editor of the online film lovers' guide Cinescene for ten of them. He currently reviews films for Flicks, a weekly program on Tucson's community radio station KXCI, and he confesses to shamelessly idolizing Carl Dreyer, Jean Renoir, and Luchino Visconti.

The only clear, confirmed photograph of the outlaw known as Billy the Kid

The only clear, confirmed photograph of the outlaw known as Billy the Kid

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.