Much of the documentary "It's a Girl" was filmed in China and India

Much of the documentary "It's a Girl" was filmed in China and India

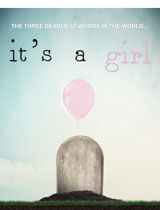

A new documentary called It’s a Girl takes a closer look at a global issue about which many Americans may be unaware.

In some South Asian nations, particularly India and China, a variety of social and legal pressures have instigated a culturally condoned practice of ‘gendercide’.

This means that female infants are aborted, killed, or abandoned at a rate that the film's producers describe as "staggering".

Filmmaker Evan Grae Davis

Filmmaker Evan Grae Davis

For the last decade and a half, Tucson-based filmmaker Evan Grae Davis has worked with nonprofit groups around the world, investigating social justice issues like human trafficking and the exploitation of children.

A desire to connect the dots and find the cause behind these issues led him to begin work in 2008 on his first feature-length documentary, It’s a Girl, produced by Shadowline Films.

The film contains a number of shockingly frank first-person accounts, and interviews with political and social activists who are working towards positive change. I asked Evan Grae Davis to begin by defining the term ‘gendercide’…

Listen:

The University of Arizona Department of Gender and Women's Studies and Shadowline Films co-present a screening of It’s a Girl at 6 p.m. at the Gallagher Theater on Friday, September 21st, 2012. The screening will be followed by a Q & A session with director Evan Grae Davis.

View the film's trailer:

The following text is a transcription of additional material recorded during the radio interview with It's a Girl director Evan Grae Davis:

Mark McLemore: What sorts of stories are you able to tell in this film?

Evan Grae Davis: It tells several different sides of the gendercide story, from a woman who admits to having taken the life of eight of her own daughters in the quest for a son. It tells the story of a family whose daughter was killed in a dowry related murder, so it shows that side of it as an adult woman being married into an arranged marriage. Her dowry was inadequate to please her husband’s family, then she had a daughter, they wanted a son and they ended up killing her. It tells the story of an Indian woman who fled her husband’s family to save her twin girl, her twin daughters from being forcibly aborted, and is today fighting a court battle to bring justice to her husband’s family for having broken this law against this sex determination testing.

The movie poster for "It's a Girl"

The movie poster for "It's a Girl"

It also captures a story about a girl that, a newborn baby girl that was abandoned in China and was picked up and adopted and raised by another family so it kind of shows the angle that there are people who don’t ascribe to this son preference, but do value girls and to the point that they would raise someone else’s child as their own.

[And we] tell the story of a young girl who was kidnapped from the front steps of her own home into a family who needed a bride for their son and so it captures that side of the human trafficking and the child bride kidnapping that occurs very commonly now in China. So it really tries to explore the issue from several of these different angles.

Mark McLemore: What were the biggest obstacles you encountered in trying to travel to these countries to tell this story?

Evan Grae Davis: One of the greatest obstacles was naturally finding people who were willing to share their story because clearly anyone who’s taking the life of their own child or who has participated in this practice of gendercide is going to be very reluctant to share about it, so I think the greatest challenge was just finding the stories, getting connected to them and then…and finding people willing to share them.

There’s a natural sensitivity, especially in China, of the danger of coming out, of publicizing your story. Our first concern obviously was the protection of those who were willing to share their story, not wanting to bring more trouble to them because they were willing to help us with the project so how do we protect their identity. How do we insure that their willingness to help doesn’t cause them a lot more trouble? So that was probably the biggest challenge we ran into.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.